|

|

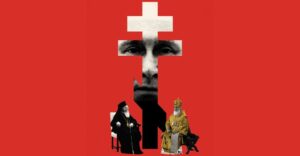

| His All Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew addresses the heads of the Orthodox churches in the Patriarchal Cathedral of Saint George.

(Photo by N. Manginas) |

His All Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew addressed the leaders of the world’s Orthodox churches on Friday, October 10, 2008, for the official opening of the Synaxis of the Heads of the Orthodox Churches and Pauline Symposium. The three-day meeting is being held at the Patriarchal Cathedral of Saint George in Istanbul, Turkey. The church leaders will later travel to sites visited by Saint Paul in Turkey and Greece later this week.

Photos of the synaxis can be viewed in the Archon photo gallery. The address of His All Holiness can be read in its entirety below:

Address by His All Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew at the Synaxis of the Heads of Orthodox Churches

Phanar, October 10, 2008

1. We offer praise and glory to the Trinitarian God that we have been counted worthy once again to gather in the same place, here at this Sacred Center, as persons entrusted by His mercy with the ministry of leadership in the local most holy Autocephalous and Autonomous Orthodox Churches, in order to affirm our sacrosanct unity in Christ and deliberate on matters that concern the Church in the fulfillment of its mission within the contemporary world.

It is with much gladness and ineffable joy that our most holy Church of Constantinople and we personally welcome you all, the most venerable and reverend Heads of the local most holy Orthodox Churches, as well as the representatives of those unable to attend in person, together with your honorable entourages. We greet each one of you warmly with a sacred embrace, exclaiming with the Psalmist: “How wonderful and sweet it is for brethren to dwell in the same place.” We express our gratitude to all of you for responding with eagerness and fraternal love to the invitation of our Modesty that we might assemble here; for you have undergone sacrifice and toil in order to travel to our City. We deeply appreciate this response on your part as evidence of brotherly love, but also of concern for the support and reaffirmation of unity within the most holy Orthodox Church, for whose unity we have been assigned guardians, keepers and guarantors by divine grace.

|

|

| The Ecumenical Patriarch addresses Orthodox leaders during the official opening of the symposium.

(Photo by D. Panagos) |

2. From the moment that, by God’s mercy, we assumed the reins of this First Throne among Churches, we have regarded it as our sacred obligation and duty to strengthen the bonds of love and unity of all those entrusted with the leadership of the local Orthodox Churches. Thus, in response also to the desire of other brothers serving as Heads, we took the initiative of convoking several occasions for Synaxis: first, in this City on the Sunday of Orthodoxy in 1992; then, on the sacred island of Patmos in 1995; and thereafter, we had the blessing of experiencing similar encounters and concelebrations in Jerusalem and the Phanar on the occasion of the beginning and end of the year 2000 as we entered this third millennium of the Lord’s era.

Of course, these occasions for Synaxis do not comprise an “institution” by canonical standards. As known, the sacred Canons of our Church assign the supreme responsibility and authority for decisions on ecclesiastical matters to the Synodical system, wherein all hierarchs in active ministry participate either in rotation or in plenary. This canonical establishment is by no means substituted by the Synaxis of the Heads of Churches. Nevertheless, from time to time, such a Synaxis is deemed necessary and beneficial, especially in times like ours, when the personal encounter and conversation among responsible leaders in all public domains of human life is rendered increasingly accessible and essential. Therefore, the benefit gained from a personal encounter of the Heads of the Orthodox Churches can, with God’s grace, only prove immense.

3. This Synaxis, beloved brothers in the Lord, occurs within the context of a great anniversary for the Orthodox Church and, indeed, for the entire Christian world. While the precise date of the birth of St. Paul, the Apostle to the Gentiles, is not known, it is conventionally estimated around the year 8AD, namely two thousand years ago. This has led other Christian Churches, such as the Roman Catholic Church, to dedicate the present calendar year as the Year of St. Paul; it was clear that the Orthodox Church, which owes so much to this supreme Apostle, could not do otherwise.

The first and greatest obligation to St. Paul is the preaching and entire Apostolic ministry of this “chosen vessel of Christ” in founding the Churches that today lie within the jurisdiction of the Orthodox Patriarchates and Autocephalous Churches, for example in Asia Minor, Antioch, Cyprus and Greece. Bearing this obligation in mind, the Ecumenical Patriarchate decided to organize a journey of pilgrimage in certain regions within its canonical confines where St. Paul preached, and fraternally to invite thereto the other Heads of the most holy Orthodox Churches in order that together we may honor the infinite labors and sacrifices, as well as all that was endured and realized by St. Paul “with far greater labors, far more imprisonments, with countless floggings, and often near death … on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from bandits, danger from [his] own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers; in toil and hardship, through many sleepless nights, hungry and thirsty, often without food, cold and naked.” (2 Cor. 11.23-7) And all this with in order to found and establish the Churches, whose pastoral care and direction the Lord’s mercy has also assigned to us.

Another obligation before St. Paul’s “labor of love” relates to his teaching, articulated in his epistles and the “Acts of the Apostles” written by his coworker in the Gospel, St. Luke the Evangelist. This teaching expresses “the exceptional character of the revelations” (2 Cor. 12.7), of which St. Paul was counted worthy by the grace of the Lord, and has remained through the centuries a guide and compass for the Church of Christ, the foundation of the doctrines of our faith, and an inviolable rule of faith and life for all us Orthodox Christians. The theology of the Church has always drawn and will continue to draw from the depth and breadth of concepts in St. Paul’s teaching.

4. This is why we deemed it appropriate, in the context of these Pauline celebrations, to organize an international and inter-Christian scholarly symposium, where select participants from the Orthodox Church and from other Christian Churches and Confessions may address and analyze topics related to various dimensions of St. Paul’s life and teaching as we journey in pilgrimage and visit the sacred places where the Apostle to the Gentiles preached and ministered. The texts of their presentations will be published in a special volume, which will hopefully contribute to Pauline studies.

As will undoubtedly become clear from the proceedings of this symposium, the teaching of St. Paul does not simply concern the past; it has — today as ever — immediate relevance in our times. For our own Synaxis in particular, this teaching is extremely significant, chiefly with regard to one of its fundamental aspects, namely its emphasis on the crucial and always topical subject of the unity of the Church, which — as we mentioned earlier — constitutes a great responsibility and concern for all Bishops in the Church, and especially the Heads of Churches.

5. St. Paul is perhaps the first theologian of Church unity. Since its foundation, the Church experienced unity as a fundamental feature of its life. After all, this was an explicit desire of the Church’s founder, expressed with particular emphasis in the prayer to His Father just prior to His passion: “I ask not only on behalf of these, but also on behalf of those who will believe in me through their word, that they may all be one. As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be one in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me. The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one. I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one.” (John 17.20-3) However, St. Paul is the first to develop and explore this unity in detail; and he toiled for this unity like no other among the Apostles.

Indeed, just as St. Paul preached the Gospel enthusiastically, so also did he labor for Church unity passionately. His “anxiety for all the churches” (2 Cor. 11.28) and their unity in Christ consumed his entire existence. As St. John Chrysostom observes: “He bore responsibility not only for a home but for cities, provinces, nations and the whole oikoumene; indeed, he was anxious about so many and so diverse important matters, for which he suffered alone and cared even more than a father for his children.” (PG 61.571B)

Nothing else brought such sorrow to the Apostle’s heart than the lack of unity and love among members of the Church: “If you bite and devour one another, take care that you are not consumed by one another,” he writes with great pain to the Galatians. (Gal. 5.15) Moreover, addressing the Corinthians, he appeals to them “by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that all of you be in agreement and that there be no division among you, but that you be united in the same mind and the same purpose.” (1 Cor. 1.10) When he ascertains that the faithful in Corinth are divided into parties, he cries out in sadness: “Has Christ been divided?” (1 Cor, 1.13)

Truly, then, for St. Paul, schism in the Church is as frightening and horrible as the division of Christ Himself. For, according to the great Apostle, the Church is “the body of Christ,” comprising Christ Himself. “Now you are the body of Christ and individually members of it,” he writes to the Corinthians. (1 Cor. 12.27) We all know how St. Paul insists on characterizing the Church as “the body of Christ,” an image he articulates extensively in the twelfth chapter of his first letter to the Corinthians. This concept is not metaphorical, but ontological in content. Division in the Church renders the very body of Christ divided. In fact, division is so repulsive and horrible for St. John Chrysostom, according to his interpretation of St. Paul’s letters, that he claims not even martyrdom can erase the sin of someone that causes division or insists on division.

Consequently, we could ask what St. Paul might say today if he were to encounter the indifference of so many of our contemporaries for the restoration of unity in the Church. Surely he would rebuke them harshly, as perhaps he might do with each of us in our tolerance or neglect before the numerous schisms and divisions invoking the name of Christ or even the name of Orthodoxy. One cannot properly honor St. Paul if one does not simultaneously labor for the unity of the Church.

6. It is this kind of struggle for the unity of the Church that St. Paul undertook with a view to bridging the gap between the judaizing Christian Jews and those from the Gentiles. Among the churches founded by St. Paul within the world of the Gentiles and that in Jerusalem, it is well known that there existed differences seriously threatening the fabric of the early Church. These differences were related to whether or not one should keep the precepts of the Mosaic Law, culminating especially in the practice or not of circumcision also among the gentile Christians. Paul’s attitude on this matter was particularly instructive. In his attitude, we may discern the first seeds of Church practice, which later became known in the canon law of our Orthodox Church as “economy” (or dispensation, oikonomia). Just like the Law of Moses, the Sacred Canons must be respected; nevertheless, they cannot also fail to take into consideration the human person, for which after all the Sabbath (namely, the Law) was made, in accordance with the familiar phrase of the Lord (cf. Mark 2.27). Echoing the spirit of our Lord, St. Paul insisted on his position and thereby pointed to the way of “oikonomia” in order not to disrupt Church unity by imposing unbearable burdens on the shoulders of the weak.

However, even the manner with which St. Paul chose to preserve Church unity at that very critical moment was enlightening. At Paul’s initiative, a solution was reached by convoking a Council in Jerusalem, which by the grace of the Holy Spirit ultimately safeguarded the unity of the Church (cf. Acts 15). Thus, while Paul was convinced of the correctness of his opinion, he was not satisfied in persisting on what he believed to be true. His passion for the unity of the Church led him to the only possible and valid defense of his position, which lies in the conciliar decision itself. The Church upheld this way through the ages, defining through Synods alone what is truthful and what is heretical. It is only in our times that we observe among Orthodox the phenomenon of individuals or groups vociferating their opinions, sometimes persistently opposing conciliar decisions of the Churches. Yet, according to the example of St. Paul as well as the Church through the centuries, both truth and Church unity are only preserved synodically.

7. At the same time, for St. Paul, Church unity is not merely an internal matter of the Church. If he insists so strongly on maintaining unity, it is because Church unity is inextricably linked with the unity of all humanity. The Church does not exist for itself but for all humankind and, still more broadly, for the whole of creation.

St. Paul describes Christ as the “second” or “final” Adam, namely as humanity in its entirety (cf. 1 Cor. 15.14 and Rom. 5.14). And “just as all die in Adam, so all will be made alive in Christ.” (1 Cor. 15.22; cf. Rom. 5.19) Just as the human race is united in Adam, so also “all things are gathered up in [Christ], both things in heaven and things on earth.” (Eph. 1.10) As St. John Chrysostom remarks, this “gathering up” (or recapitulation, anakephalaiosis) signifies that “one head had been established for all, namely the incarnate Christ, for both humans and angels, the human and divine Word. And he gathered them under one head so that there may be complete union and contiguity.” (PG 62.16)

Nevertheless, this “recapitulation” of the entire world in Christ is not conceived by St. Paul outside the Church. As he explains in his letter to the Colossians (1.16-18), in Christ “all things in heaven and on earth were created and … in him all things hold together” precisely because “he is the head of the body, the Church.” “[God] has made him the head over all things for the Church, which is his body, the fullness of him who fills all in all.” (Eph. 1.22-3) For St. Paul, then, Christ is the head of all — of all people and all creation — because He is at the same time head of the Church. The Church as the body of Christ is not fulfilled unless it assumes in itself the whole world.

There are many useful conclusions that we may gain from this ecclesiology of St. Paul. We confine ourselves to pointing out, first, the importance — for the life of the Church in general and for the ministry of us all in particular — of the duty of mission. The evangelization of God’s people, as well as of those who do not believe in Christ, constitutes the supreme obligation of the Church. This obligation — at least, when it is not realized aggressively (as was the case in the past, primarily in Western Christianity) or deceptively (as is the case with various forms of proselytism) but with love, humility and respect for the cultural particularity of each person — responds to the Lord’s desire that, through the unity of the Church, “the world may believe” in Him. (John 17.21) So we must in every way encourage and support the external mission of the Church wherever it is practiced, particularly in the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Alexandria within the vast continent of Africa.

However, even within our Churches, the need and obligation to evangelize is today rendered imperative. We must become conscious of the fact that in contemporary societies, especially in the context of western civilization, faith in Christ can in no way be taken at all for granted. Orthodox theology cannot today be developed or expounded without dialogue with modern currents of philosophical thought and social dynamics, as well as with various forms of art and culture of our times. In this regard, the message and overall word of Orthodoxy cannot be aggressive, as it often unfortunately is; for this is of no benefit at all. Rather, it must be dialectical, dialogical and reconciliatory. We must first understand other people and discern their deeper concerns; for, even behind disbelief, there lies concealed the search for the true God.

Finally, the connection between the unity of the Church and the unity of the world, on which the Apostle to the Gentiles insists, imposes on us the need to assume the role of peacemaker within a world torn by conflicts. The Church cannot — indeed, it must not — in any way nurture religious fanaticism, whether consciously or subconsciously. When zeal becomes fanaticism, it deviates from the nature of the Church, particularly the Orthodox Church. By contrast, we must develop initiatives of reconciliation wherever conflicts among people either loom or erupt. Inter-Christian and inter-religious dialogue is the very least of our obligations; and it is one that we must surely fulfill.

However, the modern world is unfortunately plagued by a crisis that cannot be reduced to inter-personal relations but extends to the relationship between humanity and the natural environment. According to St. Paul, as we have already observed, Christ constitutes the head of all, of things visible and invisible, namely of all creation, while the Church as His body unites not only humanity but the whole of creation. Therefore, it is abundantly clear that the Church cannot remain idle before the crisis that affects humanity in relation to the natural environment. It is our obligation to assume every possible initiative: first, so that our own flock may become aware of the demand for respect toward creation by avoiding any abuse or irrational use of natural resources; second, so that we may support every effort that aspires to the protection of God’s creation. For, as everyone acknowledges, the cause of the ecological crisis is profoundly spiritual, primarily due to human greed and indulgence, which characterize modern man. With its long ascetic tradition and liturgical ethos, the Orthodox Church can contribute greatly to confronting the ecological crisis that now threatens our planet. In full recognition of this, the Ecumenical Patriarchate has — already since 1989, as the first church to do so in the Christian world — issued an Encyclical signed by our venerable predecessor Patriarch Dimitrios, establishing September 1st of each year as a day of prayer for the protection of the natural environment. It has also, since that time, promoted a series of activities, such as the organization of international symposia involving scholars and religious leaders in order to ascertain ways of protecting God’s creation from imminent destruction. We invite and appeal to all sister Orthodox Churches to support this endeavor of our Patriarchate; after all, our obligation and responsibility before God and History is something we all bear in common.

8. And now, beloved brothers in the Lord, let us turn our thought to the internal affairs of our Orthodox Church, whose leadership the Lord’s mercy has entrusted to us. We have been deigned by our Lord to belong to the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church, whose faithful continuation and expression in History is our Holy Orthodox Church. We have received and preserve the true faith, as the holy Fathers have transmitted it to us through the Ecumenical Councils of the one undivided Church. We commune of the same Body and Blood of our Lord in the Divine Eucharist, and we participate in the same Sacred Mysteries. We basically keep the same liturgical typikon and are governed by the same Sacred Canons. All these safeguard our unity, granting us fundamental presuppositions for witness in the modern world.

Despite this, we must admit in all honesty that sometimes we present an image of incomplete unity, as if we were not one Church, but rather a confederation or a federation of churches. This is largely a result of the institution of autocephaly, which characterizes the structure of the Orthodox Church. As is known, this institution dates back to the early Church, when the so-called “Pentarchy” of the ancient Apostolic Sees and Churches — namely, of Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem — was still valid. The communion or “symphony” of these Sees expressed the unity of the universal Church in the oikoumene. This Pentarchy was severed after the tragic schism of 1054AD between Rome and Constantinople originally, and afterward between Rome and the other Patriarchates. To the four Orthodox Patriarchates that remained after the Schism, from the middle of the second millennium to this day, other autocephalous Churches were added until we have the prevailing organization of the Orthodox Church throughout the world today.

Yet, while the original system of Pentarchy emanated from respect for the apostolicity and particularity of the traditions of these ancient Patriarchates, the autocephaly of later Churches grew out of respect for the cultural identity of nations. Moreover, the overall system of autocephaly was encroached in recent years, through secular influences, by the spirit of ethnophyletism or, still worse, of state nationalism, to the degree that the basis for autocephaly now became the local secular nation, whose boundaries, as we all know, do not remain stable but depend on historical circumstance. So we have reached the perception that Orthodoxy comprises a federation of national Churches, frequently attributing priority to national interests in their relationship with one another. In light of this image, which somewhat recalls the situation in Corinth when the first letter to the Corinthians was written, the Apostle Paul would ask: has Orthodoxy been divided? This question is also posed by many observers of Orthodox affairs in our times.

Of course, the response commonly proffered to this question is that, despite administrational division, Orthodoxy remains united in faith, the Sacraments, etc. But is this sufficient? When before non-Orthodox we sometimes appear divided in theological dialogues and elsewhere; when we are unable to proceed to the realization of the long-heralded Holy and Great Council of the Orthodox Church; when we lack a unified voice on contemporary issues and, instead, convoke bilateral dialogues with non-Orthodox on these issues; when we fail to constitute a single Orthodox Church in the so-called Diaspora in accordance with the ecclesiological and canonical principles of our Church; how can we avoid the image of division in Orthodoxy, especially on the basis of non-theological, secular criteria?

We need, then, greater unity in order to appear to those outside not as a federation of Churches but as one unified Church. Through the centuries, and especially after the Schism, when the Church of Rome ceased to be in communion with the Orthodox, this Throne was called — according to canonical order — to serve the unity of the Orthodox Church as its first Throne. And it fulfilled this responsibility through the ages by convoking an entire series of Panorthodox Councils on crucial ecclesiastical matters, always prepared, whenever duly approached, to render its assistance and support to troubled Orthodox Churches. In this way, a canonical order was created and, accordingly, the coordinating role of this Patriarchate guaranteed the unity of the Orthodox Church, without in the least damaging or diminishing the independence of the local autocephalous Churches by any interference in their internal affairs. This, in any case, is the healthy significance of the institution of autocephaly: while it assures the self-governance of each Church with regard to its internal life and organization, on matters affecting the entire Orthodox Church and its relations with those outside, each autocephalous Church does not act alone but in coordination with the rest of the Orthodox Churches. If this coordination either disappears or diminishes, then autocephaly becomes “autocephalism” (or radical independence), namely a factor of division rather than unity for the Orthodox Church.

Therefore, dearly beloved brothers in the Lord, we are called to contribute in every possible way to the unity of the Orthodox Church, transcending every temptation of regionalism or nationalism so that we may act as a unified Church, as one canonically structured body. We do not, as during Byzantine times, have at our disposal a state factor that guaranteed — and sometimes even imposed — our unity. Nor does our ecclesiology permit any centralized authority that is able to impose unity from above. Our unity depends on our conscience. The sense of need and duty that we constitute a single canonical structure and body, one Church, is sufficient to guarantee our unity, without any external intervention.

In consideration of all these things, and with a sense of our Church’s obligation before God and History in an age when the unified witness of Orthodoxy is judged crucial and expected by all, we invite and call on you fraternally that, with the approval also of our respective Holy Synods, we may proceed to the following necessary actions:

- To advance the preparations for the Holy and Great Council of the Orthodox Church, already commenced through Panorthodox Pre-Conciliar Consultations.

- To activate the 1993 agreement of the Inter-Orthodox Consultation of the Holy and Great Council in order to resolve the pending matter of the Orthodox Diaspora.

- To strengthen by means of further theological support the decisions taken on a Panorthodox level regarding participation of the Orthodox Church in theological dialogues with non-Orthodox.

- To proclaim once again the vivid interest of the entire Orthodox Church for the crucial and urgent matter of protecting the natural environment, supporting on a Panorthodox level the relative initiative of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

- To establish an Inter-Orthodox Committee for the study of matters arising today in the field of bioethics, on which the world justifiably also awaits the Orthodox position.

We deemed it proper to offer these proposals for your consideration in our desire that this Synaxis, after exchanging more general thoughts, may also conclude with several specific decisions, whereby the unity of our Church will be expressed in deed. After all, this is what public opinion expects of us, both among our own flocks but also in the world around us. You are certainly able to add other proposals to these, should this be deemed necessary, Your Beatitudes and most eminent brothers.

In closing our address, we express once again glory to our all-good God, for vouchsafing that we convene in the same place within the context of the Pauline celebrations, and pray that our brotherly fellowship in the Lord during these days will unite us still more in the bond of love.

“Now to Him who by the power at work within us is able to accomplish abundantly far more than all we can ask or imagine; to Him be glory in the Church and in Christ Jesus.” (Eph. 3.20-1) Amen.

|

View photos of the Synaxis of the Heads of Orthodox Churches |