The news service, Forum 18, recently reported on the newly-revised Foundations Law which the Turkish Parliament has passed. Originally adopted by Parliament in 2006 under heavy pressure from the European Union, the law returns properties confiscated by the state to non-Muslim religious minority foundations and also allow these foundations to receive financial aid from foreign countries.

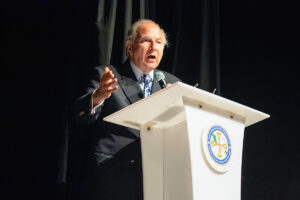

However, Dr. Otmar Oehring, head of the Human Rights Office of the German Catholic charity Missio, offers an extensive overview on how the law does not allow Muslim or non-Muslim religious communities to legally exist as themselves or allow them to own their own places of worship. He argues that the way to guarantee freedom of thought, conscience and belief is to make the European Convention on Human Rights’ commitments a concrete reality in Turkey.

The Forum 18 news service report on serious and obvious breaches of religious freedom, particularly on situations where the lives and welfare of individual people or groups are being threatened and where the right to gather around one’s faith is being hindered. They aim to ensure that threats and actions against religious freedom are truthfully reported as quickly as possible across the world.

The published article on Forum 18 can be read in its entirety below.

Turkey: What difference does the latest Foundations Law make?

By Dr. Otmar Oehring, Head of the Human Rights Office of Missio

3/13/2008

Read this article on www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=1100

Turkey has passed the long-promised new Foundations Law. However, it does not allow Muslim or non-Muslim religious communities to legally exist as themselves, Otmar Oehring of the German Catholic charity Missio notes in a commentary for Forum 18 News Service. Bizarrely, religious communities are therefore not themselves allowed to own their own places of worship. For most non-Muslim communities, these are owned by community foundations. This leads to serious problems. For example, only the state can legally make even basic building repairs. As Dilek Kurban of the respected Turkish TESEV Foundation noted, the Law is “incompatible with the principle of freedom of association, which is guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights, the Constitution and the [1923] Treaty of Lausanne”. Dr Oehring argues that the way to guarantee freedom of thought, conscience and belief is to make the European Convention on Human Rights’ commitments a concrete reality in Turkey.

Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan finally managed to push the long-promised revised Foundations Law (No. 5737) through a reluctant parliament in mid-February. President Abdullah Gul signed it into law on 26 February. The new Law will make life slightly easier for the community foundations allowed to some of Turkey’s non-Muslim communities, which the Turkish Republic has always understood in ethnic/religious terms. Yet it does nothing to change the legal position of non-Muslim religious communities.

As before, religious communities themselves – including Muslims – have no legal status in their own right and therefore no right to own property in their own name. Sadly, the many observers who are not legal specialists fail to realise this – and its huge implications for the life of Turkey’s non-Muslim religious communities.

Indeed, a closely-argued analysis of the then-draft Foundations Law – prepared in December 2007 by Dilek Kurban of the Istanbul-based TESEV Foundation http://www.tesev.org.tr on the basis of views from Turkey’s smaller communities – criticised many elements of it. The TESEV analysis noted that although provisions in the Law “introduce some improvement, they are far from solving the most basic and urgent problems of these foundations”. It also warned that some provisions might “pose the risk of exacerbating the existing problems of non-Muslim foundations and providing legal legitimacy to unlawful bureaucratic practices”.

Laws and bureaucratic practices operate in a social context which, in Turkey, has seen violent attacks on and even murders of members of the country’s smaller communities. Three trends have been identified as lying behind this intolerance and violence: disinformation by public figures and the mass media; the rise of Turkish nationalism; and the marginalisation of smaller groups from Turkish society. All three trends feed off each other, and all of Turkey’s smaller religious communities – those within Islam and Christianity, as well as Baha’is and Jehovah’s Witnesses – are affected by this (see F18News 29 November 2007 http://www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=1053).

The new Foundations Law allows – in theory – community foundations (which only belong to some non-Muslim communities) to apply to recover seized properties, if they are still in the hands of the state, and Muslim and non-Muslim foundations to receive foreign funding. It also theoretically permits non-Muslim foundations to “engage in international activities and opportunities for cooperation, establish branches and representation offices abroad, set up umbrella organisations and become members of organisations established abroad,” on condition that these activities are mentioned in their charter (vakif senedi).

However, Kurban of the TESEV Foundation has pointed out that non-Muslim foundations do not have charters. The term and legal status of community foundation was invented by the Turkish Republic to provide a legal framework for the properties of non-Muslim minorities that existed in Ottoman times. For all these properties, the only legal document that existed and referred to the ownership was a decree (firman) issued by one of the sultans granting the right to a piece of land and – for example – to build a church on it. So as Kurban noted, “non-Muslim foundations cannot satisfy the condition set forth by the Law.” She described this as “an example of direct discrimination against non-Muslim foundations” and “incompatible with the principle of freedom of association, which is guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights, the Constitution and the [1923] Treaty of Lausanne.”

The new Law has had a tortuous passage. Originally adopted by parliament in 2006 under heavy pressure from the European Union (EU), it was promptly vetoed by the then President Ahmet Necdet Sezer, a committed secularist, who complained that “it could serve to strengthen minority foundations”. It was reintroduced to parliament in spring 2007 but the process soon ground to a halt (see F18News 10 July 2007 http://www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=990). After the July 2007 parliamentary election and the appointment of a new president, work on the Foundations Law was revived. The text approved by parliament in early February 2008 was the same as the text vetoed by President Sezer.

Media reports indicate that unhappiness over the new Foundations Law remained endemic, with many in the ruling party, the Justice and Development Party (AKP), opposed. Also opposed were members of other parties, especially the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). Erdogan was probably afraid to go any further than he did. Many thought earlier that he was prepared to end smaller religious communities’ problems, especially over their “seized properties”, but it seems he thought this would have been too costly for the state in financial compensation to those communities. Few in society would have welcomed large-scale state compensation for injustices such as property seizures.

It is possible to argue that some good will come of this Law – at the least it demonstrates that the current government is keen to show that it is concerned for the country’s non-Muslim communities. Yet whether this is a real concern or merely a show for the outside world is not known.

The new Law covers foundations of all kinds – including Muslim foundations – under the control of the Directorate-General for Foundations, not only those allowed to some of Turkey’s non-Muslim communities. Many Muslim foundations exist, for example those that offer food to the poor in exchange for their prayers for the deceased founder. In recent years many large companies have launched charitable foundations. But the focus of most comment, inside and outside Turkey, has been on the foundations of the non-Muslim communities.

Mosques are mostly the property of the so-called Diyanet Vakfi, which is a foundation (vakif) under the Civil Code, established on 13 March 1975. Its purpose is to foster knowledge of Islam and religion, to build mosques where necessary, and to support people in need (see its website http://www.diyanetvakfi.org.tr). The President of the board is Professor Ali Bardakoglu, who also heads the Presidency of Religious Affairs, or Diyanet (see F18News 12 October 2005 http://www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=670). There are also mosques which are owned by, for example, municipalities.

The non-Muslim religious communities are generally not allowed to own property – the handful of exceptions are those that have slipped through over the years and exist in a legal grey zone (see F18News 13 December 2005 http://www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=704). For example, the Istanbul Protestan Kilisesi Vakfi (http://www.ipkv.org) was founded on 10 November 1999. According to the State Gazette, this gained legal recognition on 24 June 2001 in accordance with the Civil Code.

However, Article 101 of the Civil Code does not allow the establishment of a foundation with a religious goal. In 2005, the Supreme Court of Appeals in Ankara finally rejected the Seventh-day Adventist Church’s application to establish a foundation, basing its judgment on Article 101. The Court found that the purpose of the foundation was to “meet the religious needs of Turkish citizens who adopt the beliefs of Seventh-day Adventists, and foreigners of the same belief who are domiciled or are temporarily staying in Turkey”, which it regarded as unacceptable and illegal.

This argument could even be applied to the Diyanet Vakfi, whose goals include “fostering Islam and the building of mosques”. The court’s argument could also be applied to the Istanbul Protestan Kilisesi Vakfi and to the Syrian Catholic Church Foundation. This latter foundation uses property in Istanbul seized from the Jesuits. According to the Turkish state, this is now the property of the State Treasury and is separate from the Syrian Catholic community foundation.

In Ottoman times the then existing non-Muslim communities were allowed to acquire property on the basis of a firman issued by the Sultan. These covered only Armenian Catholic, Armenian Apostolic, Armenian Protestant, Bulgarian Orthodox, Chaldean Catholic, Georgian Catholic, Greek Catholic, Greek Melkite Orthodox, Jewish, Syrian Catholic, Syrian Orthodox and Syrian Protestant foundations. After the foundation of the Turkish Republic in 1923, community foundations were created by the state as a legal framework for those properties. Such foundations typically owned not just places of worship but religious colleges, hospitals, orphanages and old people’s homes. Some have been given property since 1923 – such as private homes bequeathed to foundations in wills – which they use as sources of funds, but most properties are directly used to provide community services.

The situation of Latin-rite Catholics is different, as they were in Ottoman times under the protection of the non-Turkish “Powers”. Therefore the Latin-rite Catholic Church has today no community foundations, which is a major problem. Land-titles do exist for many Latin-rite Catholic properties, but it is unclear whether or not these are recognised by the state. This is because the Turkish state does not legally recognise either the Latin-rite Catholic Church or Catholic religious orders. And an owner who does not legally exist cannot legally own property.

No new community foundations have been permitted to be started since the state created the legal framework of community foundations. Because of the origins and ethnic/religious ownership of the community foundations, this perpetuates the Ottoman-era idea that people of one ethnicity can only belong to one faith. So, ethnic Turks cannot be anything other than Sunni Muslims (preferably Sunni rather than Alevi). Turkish nationalists today strongly promote this idea, which has dangerous consequences for Turkish citizens who are not Sunni Muslim Turkish nationalists (see F18News 29 November 2007 http://www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=1053).

Turkish government hostility to non-Muslim communities led over the decades since the foundation of the Republic to tight control over the Boards which ran the community foundations, a de facto ban on maintaining their property in good repair and the stripping away of much of the property under various pretexts. The state would often remove Board members it did not like.

If all the Board members died the state would often prevent new members being appointed and seize the property. The state often argued that a community foundation no longer needed its facilities and confiscated them. The TESEV report notes that the Greek Orthodox have suffered the most from such seizures – they say 24 community foundations and hundreds of properties they owned have been seized. One Greek Orthodox community foundation had its property on one of the Princes’ Islands seized and handed to a Muslim foundation, which the Greek Orthodox are still trying to challenge through the courts (see F18News 18 January 2007 http://www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=901).

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in January 2007 found in favour of a Greek Orthodox community foundation (Fener Rum Erkek Lisesi Vakfi), whose high school buildings had been seized. The ECHR imposed a large fine on the Turkish government. In the similar case of the Armenian Yedikule Surp Pirgic Ermeni Hastanesi Vakfi, the Turkish government in June 2007 reached a friendly settlement with the foundation (see F18News 10 July 2007 http://www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=990). The Greek Orthodox foundation has received the fine awarded by the ECHR, which so far as the foundation is concerned settles the case, and the Armenian foundation has now received both its costs and the return of its buildings.

Such arbitrary seizures seem to have stopped in recent years, though lack of information about every community foundation makes it difficult to be sure. Muslim foundations have faced no such problems.

The new Law will – at least in theory – allow community foundations to apply to recover these “seized properties”, provided they are still in the hands of the state. This is a positive step. However, thousands of community foundation buildings – now worth millions of Euros – were seized by the state over decades and have now been sold on to third parties. The new Law makes no provision for their return or for possible compensation in lieu.

However, one Turkish observer suggested to Forum 18 on 12 March that – as in the cases of the Greek Orthodox Fener Rum Erkek Lisesi Vakfi and Armenian Yedikule Surp Pirgic Ermeni Hastanesi Vakfi – the ECHR in Strasbourg is now the best route to resolving past property seizures. This suggestion matches my own observations of the situation (see F18News 18 January 2007 http://www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=901).

The government’s insistence that only non-Muslim communities recognised before 1923 can own property leads to the bizarre consequence that a religious community and its leaders have no legal control over the worship buildings they use. In hierarchical communities – such as the Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches – this means the bishop has no control over places of worship. Normally, such leaders do have jurisdiction over their community’s property.

The Greek Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul’s Fener District – the seat of the most senior cleric in the Orthodox world – has no legal status and does not own its own headquarters. A community foundation owns the land and the older buildings – including the Patriarchal Church of St George. But the legal status of the imposing new patriarchal offices – which the Turkish authorities allowed to be rebuilt only in the late 1980s, nearly fifty years after they were burnt down – has never been clarified. The building is not listed on the land register.

The building of the Halki Seminary – the Greek Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarchate’s world-renowned theological college until, along with the Armenian Seminary, it was forced to close by the government in 1971 – also remains in the hands of a community foundation. If, as the Patriarchate sincerely hopes, the government allows it to reopen, again the Church which uses the building will not be the formal owner of it.

The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate – as the Turkish state refuses to use the word “Ecumenical” – is described on the land register as the formal owner only of a handful of properties. Yet the Turkish authorities refuse to acknowledge even this direct ownership. Indeed, a case over a directly-owned orphanage at Buyukada is now with the ECHR in Strasbourg.

Perhaps it is Islam’s lack of a formal hierarchy that leads Turkish officials to fail to recognise that other religious communities may be structured differently. In particular, they fail to understand the needs of hierarchically-organised religious communities.

The particular problem for places of worship owned by community foundations is that the religious community cannot even repair holes in the roof, or repaint the interior, let alone restore or extend them. Under the Treaty of Lausanne, which enshrined ethnic/religious community rights, such repairs are the responsibility of the state. The Directorate-General for Foundations had to decide if such repairs were necessary – and invariably said they were not. State hostility to non-Muslim communities since 1923 has meant that the state has undertaken no such repairs. The state was waiting until such properties fell apart and all the people died or left the country.

Officials have recently pledged to repair community foundations’ property, but it is unknown if they will keep their word.

For decades priests were afraid to go ahead and make even urgent repairs unilaterally when churches needed them. Such fear was even more engrained in schools, which are forced to have an ethnic Turk as deputy director. Since the 1990s, such redecoration or repairs require municipal approval, which has gradually become easier to obtain. The police normally turn a blind eye to these breaches of the law.

Yet such petty controls are absurd. Either the state should carry out repairs, in which case it should make sure properties are well-maintained, or should leave the community foundations to get on with them unobstructed.

The new Law should make it easier for community foundations to sell their properties if they wish to and use the money to maintain other properties.

The refusal to allow non-Muslim communities legal status as such leaves them vulnerable over property. Religious communities without community foundations – such as the Latin-rite Catholics or the Presbyterian Churches, as well as communities that have existed in Turkey only recently, such as Baha’is, Jehovah’s Witnesses and many Protestant denominations – have only a precarious legal hold on their property that could be challenged in court by malicious officials or individuals.

Latin-rite Catholics (a special case owing to their pre-1923 status) own their churches and some other property directly, but as indicated above with little legal security.

A change to the Associations Law in 2004 allowed religious communities to gain legal status as associations, a route recently followed – albeit with difficulty – by some Protestants and Jehovah’s Witnesses (see F18News 12 October 2005 http://www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=670). In theory such associations have legal personality and can own property in their own name, though religious communities have problems asserting these rights.

Protestant churches built by individual pastors in recent years have often been subjected to protracted and tortuous legal battles to be allowed to use them officially. Some have been successful, though again the legal ownership and use is never secure in law. Other Protestant churches meet in what is officially domestic or office premises – which technically is illegal.

Turkey missed an opportunity to resolve the lack of legal status for non-Muslim communities and the impossibility for them to gain secure property rights. In 2003 an official in the Foreign Ministry in Ankara asked a respected Istanbul law professor to prepare a draft Foundations Law that would have resolved these problems. The idea was to remove the restrictions through an amended law in a quiet way, so as not to arouse the attention and wrath of Islamists and nationalists. The authorities later suppressed or – to put it more mildly – buried this proposed draft. The issue was too hot for them.

It remains to be seen how this new Foundations Law will be implemented. Some members of the smaller communities have already complained – as did the TESEV report – of Article 2 (2), which specified that “reciprocity shall be reserved in the implementation of this law”. They question the inclusion of this Article, given that the foundations were established and are run by Turkish citizens for Turkish citizens. They fear the government will use the continuing (and unjust) restrictions on Greece’s Turkish and Muslim population to allow it to wriggle out of respecting the rights of its non-Muslim communities.

The TESEV report reserved perhaps its fiercest criticism for Article 5 (1), which subjects new foundations to the provisions of the Civil Code. Given the effective ban in its Article 101 (4) on foundations pursuing religious goals, this bars religious communities from directly establishing foundations and using them to acquire and maintain places of worship. The TESEV report insisted this violates freedom of association and called for the Article to be removed from the Law. Yet, when the Law was adopted, the Article remained. This remains a potential problem for the Protestant and other religious communities who gained legal status as associations in recent years.

So Turkey’s non-Muslim communities will not be able to gain the right to buy, sell and maintain places of worship and other property through the new Foundations Law, as this right is reserved exclusively for the existing community foundations. Their basic position has remained unchanged. They are still not free to – in accordance with international human rights standards – act as they like, do what they want to do, or organise themselves as they choose.

Abolishing Article 101 (4) of the Civil Code would be a start, but many argue that without the removal from the Turkish Constitution of the provision enshrining secularism – or even better, reshaping it to fully incorporate Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights – this too would not be enough. As a revision of the Constitution is already being discussed, amid many delays, this could in theory be done.

In my view, the best method to introduce true religious freedom in Turkey would be to introduce into the Constitution commitments to religious freedom in line with Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights – which came into force for Turkey in 1954 – and for these commitments to be made a concrete reality for all Turkish citizens. The history of Turkey’s advances towards true religious freedom clearly demonstrates this (see F18News 13 December 2005 http://www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=704).

Article 90 of the Turkish Constitution already states that: “In the case of a conflict between international agreements in the area of fundamental rights and freedoms duly put into effect and the domestic laws due to differences in provisions on the same matter, the provisions of international agreements shall prevail.” However, what seems to be lacking in Turkey is the will to translate “international agreements in the area of fundamental rights and freedoms” into concrete reality. The challenges of intolerance and violence that Turkish society faces makes this an increasingly urgent question (see F18News 29 November 2007 http://www.forum18.org/Archive.php?article_id=1053).

If the European Convention’s human rights commitments were made a living reality in Turkey, this would at least resolve the non-Muslim communities’ legal problems and also be a very significant step in addressing the serious Turkish social issues of intolerance and violence.

Dr Otmar Oehring, head of the human rights office of Missio, a Catholic charity based in Germany, contributed this comment to Forum 18 News Service. Commentaries are personal views and do not necessarily represent the views of F18News or Forum 18.