Dear Brother Archons and Friends of the Archons of the Ecumenical Patriarchate,

One of the most worthy initiatives of the Archons of the Ecumenical Patriarchate is introducing the next generation of the faithful to the Spiritual Center of world Orthodoxy, and will carry major dividends in the years to come: the Pilgrimage of Discovery (POD) program. Here is a moving and insightful example from a POD alumnus, Stavros Piperis, of how life-changing and transformative this program is for the young adults who participate in it.

We need your help to financially support this program so that we can send young adults to Constantinople every year and grow the number of young adult ambassadors to the Archons and the Ecumenical Patriarchate and create an inextricable bond between these young adults and the Mother Church.

Your annual contribution of at least $250 can make that happen. We encourage all Archons to make an offering to sustain this program. Donate to the Pilgrimage of Discovery Program here.

To see a video capturing the transformational experience, click here.

And please be sure to read all of Stavros Piperis’ inspirational article below.

Yours in the service of the Ecumenical Patriarchate,

Anthony J. Limberakis, MD

Archon Grand Aktouarios

National Commander

Archon Perry C. Siatis

Chair POD Committee

Regional Commander Metropolis of Chicago

Our Sleeping Queen of Cities: A Pilgrim’s Reflections in Constantinople

A drowsy wind blows across the blue-gray waters of the Bosphorus. On it a lone seagull flies, lilting along the air current. Behind it looms Constantinople: colossal, gleaming, age-old, alive.

I recently spent a week in the Queen of Cities with the Pilgrimage of Discovery, an immersion program sponsored by the Archons of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The Pilgrimage aims to bring young Orthodox Christians face-to-face with the situation of the Patriarchate and the remaining Greek-speaking Orthodox (or Romaioi) community in modern-day Istanbul. The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople— the spiritual capital of the Eastern Orthodox Church— currently operates on less than an acre of land behind a bustling street corner near the Golden Horn. Cars and buses whiz past, the air thick with the smell of gasoline and hot asphalt. The fact that a church of roughly 250 million Christians around the world is headquartered here, amidst the tourist shops and the bleating of car horns, is plain to no one walking by. Meanwhile, the city’s Greek-speaking Christian population, which once numbered in the hundreds of thousands, has been whittled down to only 1,500 to 3,000 people.

The humanitarian and religious liberty concerns raised by the treatment, past and present, of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and Orthodox Christians in and around Constantinople are obvious and I will not belabor them here. I focus instead on a set of images, more potent than arguments, that a week as a Greek Christian in Constantinople— the city once heralded as “the New Jerusalem”— left me with.

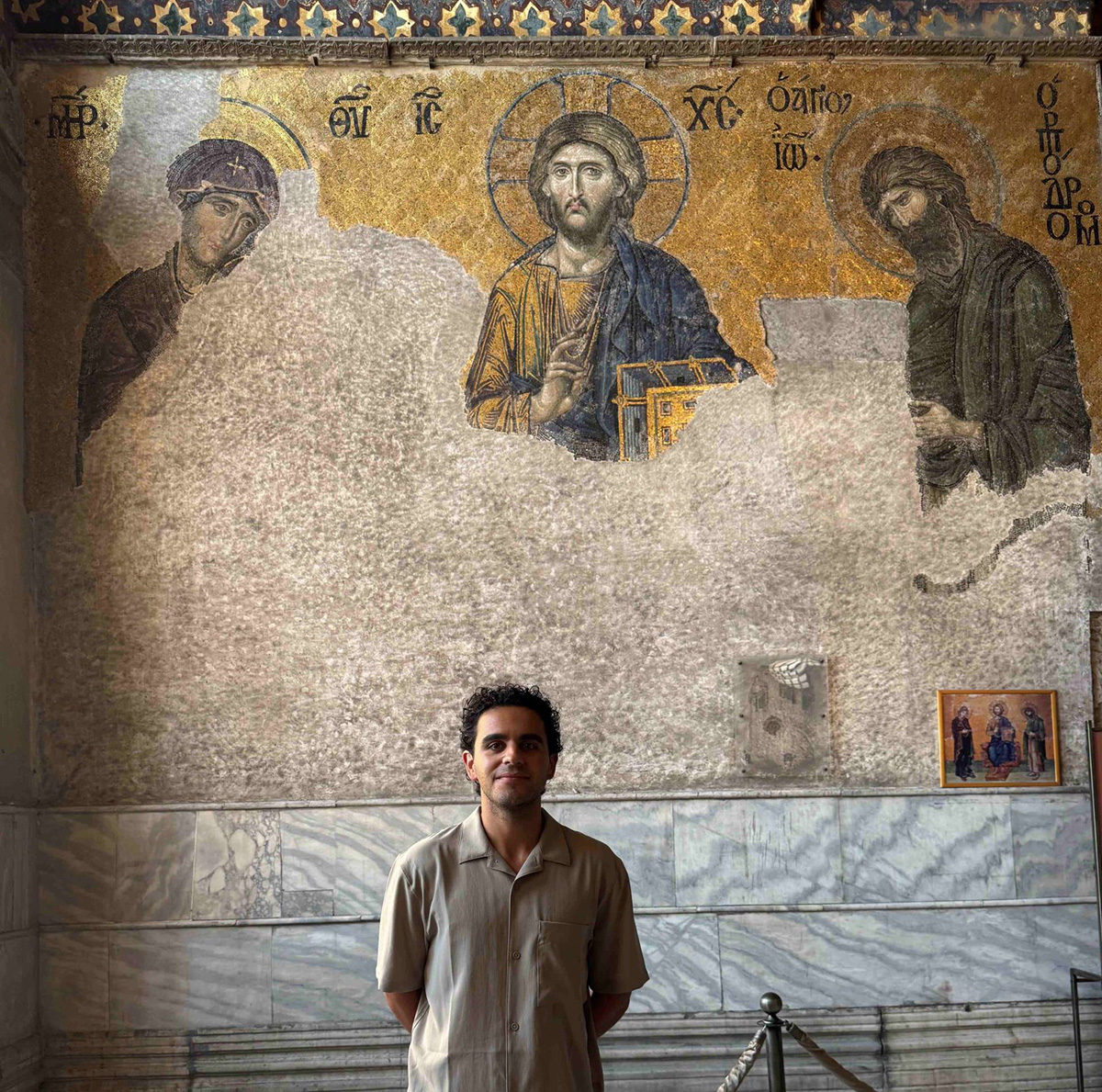

First, the iconography continues to stun. Because so much of Byzantine Constantinople has been erased, the few icons that survive to the present day stand out sharply against their modern, predominantly Muslim backdrop. The erasure has not, of course, been accidental; destruction of icons is often a top priority for invaders looking to subjugate and demoralize indigenous Orthodox Christian populations. One Ottoman chronicler emphasized after the taking of Constantinople in 1453 that “the churches which were within the city were emptied of their vile idols[] and cleansed from their filthy and idolatrous impurities” (Roger Crowley, ‘1453’, New York: Hachette Books, 2023, p. 245); the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974 similarly left many a church sacked or graffitied. In Constantinople today, some of the foremost masterpieces of the Byzantine iconographic tradition— the Deisis Mosaic in the Hagia Sophia and the frescoes in the Chora Church, for example— are irreparably damaged, either plastered over or with eyes and faces gouged and scratched beyond recognition. The Platytera icon in the Hagia Sophia, one of Orthodoxy’s most cherished depictions of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child, is draped over with fabric curtains, only partially viewable from a small nook on the building’s second floor.

Yet their power seems to me to only grow. The icons have grown more beautiful in the struggle. Perhaps to the Christian worshipper pre-1453, the Deisis Mosaic would have merely been one jewel among hundreds adorning the walls of the great cathedral. Now the icon stands in decidedly hostile territory, a defiant remnant of Byzantine greatness and achievement, an inconvenient and unwelcome memory. The damaged portions of the Deisis rise up and surround Christ, Mary, and Saint John the Baptist like the smoke of a consuming flame. I cannot help but draw meaning from the accidental effect; these three figures, who were destined for persecution on earth, are, in a real sense, at home in the fight.

It follows from all this that a Christian wishing to visit the holy sites still standing in Constantinople does so with some trepidation. Where churches have been converted into mosques, one, of course, cannot light a candle upon entry or venerate the icons openly. I signed my Cross in miniature and usually with my back turned to any security personnel. Another pilgrim on our trip walked into the Hagia Sophia with the Cross around his neck visible and was instructed to cover it up.

“Dull is the eye that will not weep to see / Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed…” Byron’s words attach as naturally to the scarred treasures of Byzantium as to the Hellenic marvels for which they were intended. But in Constantinople one is perhaps most moved by what one does not see. The outsize legacy of the Hagia Sophia is contrasted with how empty the building now feels, with so much of what used to adorn the walls painted over or destroyed. Gone is the visual splendor which once made Constantine’s city “the city of the world’s desire”: the marble, porphyry, and beaten gold, the dizzying public beauty testified to by so many medieval observers. The great squares and gardens, the pagan and Christian statutes and arches, the churches “more numerous than days of the year” (Crowley, ‘1453’, 17-18)— lost to history and hidden from view.

Nor is there any tribute to Constantine XI Palaiologos, the resolute general who would become the last emperor of Byzantium. Most historians agree that Constantine XI died fighting in the final desperate defense of the city against the Ottomans in 1453, but precise details of his death, including the location of his grave, remain elusive. Legends have spread among the Greeks to fill the gaps; according to one of them, the emperor was saved by an angel just before meeting his death in battle and turned to marble, and he now sleeps under the Golden Gate of Constantinople, awaiting God’s call to rise again and retake the city for Christendom. Sultan Mehmed II’s decision to wall up the Golden Gate after conquering the city has perhaps only amplified the prophecy.

When I think of Constantinople, I think of Constantine XI, haunted by him like so many Greeks since the walls were breached that spring morning in 1453. And I dwell upon Patriarch Bartholomew’s insistence throughout our pilgrimage— which coincided with the feast of the Transfiguration or Metamorphosis— that we endure in hope, that “the world is… transfigured by the few,” that “only that which is light is truth.”

And still, fixed in my mind is the sight of the ghostlike moon over the Bosphorus, the same moon that brooded above our ancestors for a millennium, the mother of a thousand omens.

What is Constantinople to the Greek, the Orthodox, of today? A squandered glory, a scrapheap of marble and mortar, a candle in the wind? It is our past, but also much more than that: it is a hope perched stubbornly in the Greek soul, a glimmer of “the city which is to come” (see Heb. 13:13-14), a promise past and pending, “a loom on which to spin [our] dreams” (Anthony Doerr, ‘All the Light We Cannot See’, New York: Scribner, 2017, p. 389). And it is home, though we are not welcome as we once were. Our Queen of Cities is not dead, but has been cast into a kind of fitful slumber. When will she wake? When will we?

Stavros Piperis is an attorney and writer based in Omaha and New York. He has published and presented across the country on the topics of theology and the arts.